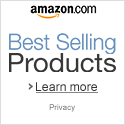

On 4 November 1979, after a popular revolution swept the Shah of Iran, a close American

ally, out of power, Iranian students backing the new revolutionary Islamic government stormed

the US embassy in Teheran and took the staff and USMC security contigent hostage.

In all, 52 Americans were captured and it was unclear whether they were being tortured or readied for execution. After six months of failed negotiation, the US broke diplomatic relations with Iran on 8 April 1980 and the newly certified US Army Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (Airborne) was put on full alert and plans were being drawn up for a rescue.

The Americans faced a daunting task. Teheran is well inside Iran and away from friendly countries. The hostages were not held at an airport as in Israel's four years earlier Entebbe raid. Good intelligence was hard to come by about forces inside the embassy and in Teheran. And of course, all the planning and training had to be carried out in complete secrecy.

In all, 52 Americans were captured and it was unclear whether they were being tortured or readied for execution. After six months of failed negotiation, the US broke diplomatic relations with Iran on 8 April 1980 and the newly certified US Army Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (Airborne) was put on full alert and plans were being drawn up for a rescue.

The Americans faced a daunting task. Teheran is well inside Iran and away from friendly countries. The hostages were not held at an airport as in Israel's four years earlier Entebbe raid. Good intelligence was hard to come by about forces inside the embassy and in Teheran. And of course, all the planning and training had to be carried out in complete secrecy.

The Plan

Codenamed Operation Eagle Claw, the initial preferred solution was the infiltration of the force by trucks from

Turkish territory but this plan was rejected due political disadvantages and the risk of a

great number of casualties made to discard the possibility of a night paratroopers assault so

the choice fell again, after all, on the use of helicopters.

By December 1979, a rescue force was selected and a training program was under way.

Training exercises were conducted through March 1980 and the Join Chiefs of Staff (JCS) approved mission execution

on 16 April 1980. Between 19 and 23 April, the forces deployed to Southwest Asia.

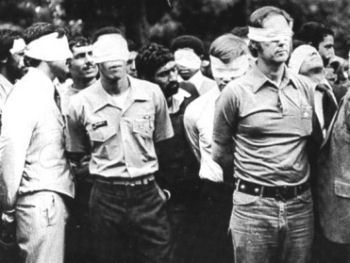

What was ultimately decided on for Operation Eagle Claw was an audacious plan involving all four US armed forces services, 8 helicopters (Navy RH-53D's with USMC crews), 12 USAF planes ( 4 special ops MC-130E Combat Talon, 3 command post EC-130E Commando Solo, 3 gunships AC-130 Spectre, and 2 cargo C-141 Starlifter ), and numerous operators infiltrated into Teheran ahead of the actual assault. Aircraft carriers USS Nimitz (CVN68) and USS Coral Sea (CV43) were already in the Arabian Sea to provide air support if necessary with their F-14A Tomcat, A-6E Intruder and A-7E Corsair.

The basic plan was to infiltrate the operators into the country the night before the assault and get them to Teheran, and after the assault, bring them home.

What was ultimately decided on for Operation Eagle Claw was an audacious plan involving all four US armed forces services, 8 helicopters (Navy RH-53D's with USMC crews), 12 USAF planes ( 4 special ops MC-130E Combat Talon, 3 command post EC-130E Commando Solo, 3 gunships AC-130 Spectre, and 2 cargo C-141 Starlifter ), and numerous operators infiltrated into Teheran ahead of the actual assault. Aircraft carriers USS Nimitz (CVN68) and USS Coral Sea (CV43) were already in the Arabian Sea to provide air support if necessary with their F-14A Tomcat, A-6E Intruder and A-7E Corsair.

The basic plan was to infiltrate the operators into the country the night before the assault and get them to Teheran, and after the assault, bring them home.

The first night, three MC-130's Combat Talon were to fly to an barren spot in Iran and

offload the Delta force men, Combat Controllers, and translators/truck drivers. Three EC-130's

following the Combat Talon's would then land and prepare to refuel the Marine RH-53's

flying in from the carrier USS Nimitz. Once the helicopters were refuled, they would fly the

task force to a spot near the outskirts of Teheran and meet up with agents already

in-country who would lead the operators to a safe house to await the assault the next night.

The helicopters would fly to another site in-country and hide until called by the Delta operators.

The helicopters would fly to another site in-country and hide until called by the Delta operators.

On the second night, the MC-130's and EC-130's would again fly into the country, this time

with 100 US Army Rangers troops, and head for Manzariyeh Airfield. The Rangers were to assault

the field and hold it so that the two C-141's could land to ferry the hostages back home.

The three AC-130's would be used to provide cover for the rangers at Manzariyeh, support Delta's

assault, and to supress any attempts at action by the Iranian Air Force from nearby

Mehrabad Airbase. Delta would assault the embassy and free the hostages, then rendevous

with the helicopters in a nearby football stadium. They and the hostages would be flown

to Manzariyeh Airfield and the waiting C-141's and then flown out of the country. All

the aircraft but the eight helicopters would be flown back, the helicopters would be

destroyed before leaving.

The Sikorsky RH-53D Sea Stallion was the specialized mine countermeasures variant ( fitted with devices for the detection, sweeping and neutralization of all types of mines ) of the CH-53 Sea Stallion . The US Navy received the first of 30 RH-53D in May 1973 to replace the old RH-3A Sea Kings and, coincidentally, the only other customer of the RH-53D was the Iranian Navy with 6 aircraft delivered to the Shah.

The determination of the type of helicopter to be used was very difficult but the Sea Stallion was selected in good part due to its great capacity to carry heavy loads. Completely supplied can take 30 people and with less fuel 50 with a maximum gross weight of 42,000 pounds (15 Tn aprox) and is capable of speeds up 160 knots. In spite of it's huge size, the Sea Stallion has been known to make a few loops from time to time.

The RH-53D variant had extra fuel tanks on the landing gear pylons so this aircraft was preferable to the normal CH-53D due it's long range. A year before, on April 1979 a RH-53D from US Navy squadron HM-12 set a new nonstop transcontinental flight by flying from Norfolk, Virginia, to San Diego, California. The helicopter flew 2,077-nm in 18.5 hours, air refueling from an Air National Guard HC-130 Hercules. The flight demonstrated the long-range, quick-response capability of the RH-53D helicopter and was commanded by Lieutenant Rodney M. Davis.

But moreover a hunting-mines helicopter would not seem outside of place on board an aircraft carrier.

In October 1979, US Navy Squadron HM-16 was participating in Canous Marcot 79, a joint U.S. - Canadian exercise, shore based at CFB Shearwater, Nova Scotia, Canada. The squadron's prime objective was to clear a simulated minefield blocking this major strategic Canadian port. Four days after returning from this Canadian deployment, HM-16 was tasked to execute a no-notice rapid deployment to the Indian Ocean area. Within a 34 hour period, all personnel and squadron assets were deployed from the commands home base in Norfolk, Virginia and stationed aboard carrier USS Nimitz where their RH-53's were painted brown for the camoflauge effect of the Iranian desert and to be similar to Iranian aircraft paint schemes.

HM-16 provided the eight helicopters for Eagle Claw and was until 19 May 1980 when the squadron returned to Norfolk after an unprecedented 193 days continuous at sea.

The Helicopters

The Sikorsky RH-53D Sea Stallion was the specialized mine countermeasures variant ( fitted with devices for the detection, sweeping and neutralization of all types of mines ) of the CH-53 Sea Stallion . The US Navy received the first of 30 RH-53D in May 1973 to replace the old RH-3A Sea Kings and, coincidentally, the only other customer of the RH-53D was the Iranian Navy with 6 aircraft delivered to the Shah.

The determination of the type of helicopter to be used was very difficult but the Sea Stallion was selected in good part due to its great capacity to carry heavy loads. Completely supplied can take 30 people and with less fuel 50 with a maximum gross weight of 42,000 pounds (15 Tn aprox) and is capable of speeds up 160 knots. In spite of it's huge size, the Sea Stallion has been known to make a few loops from time to time.

The RH-53D variant had extra fuel tanks on the landing gear pylons so this aircraft was preferable to the normal CH-53D due it's long range. A year before, on April 1979 a RH-53D from US Navy squadron HM-12 set a new nonstop transcontinental flight by flying from Norfolk, Virginia, to San Diego, California. The helicopter flew 2,077-nm in 18.5 hours, air refueling from an Air National Guard HC-130 Hercules. The flight demonstrated the long-range, quick-response capability of the RH-53D helicopter and was commanded by Lieutenant Rodney M. Davis.

But moreover a hunting-mines helicopter would not seem outside of place on board an aircraft carrier.

In October 1979, US Navy Squadron HM-16 was participating in Canous Marcot 79, a joint U.S. - Canadian exercise, shore based at CFB Shearwater, Nova Scotia, Canada. The squadron's prime objective was to clear a simulated minefield blocking this major strategic Canadian port. Four days after returning from this Canadian deployment, HM-16 was tasked to execute a no-notice rapid deployment to the Indian Ocean area. Within a 34 hour period, all personnel and squadron assets were deployed from the commands home base in Norfolk, Virginia and stationed aboard carrier USS Nimitz where their RH-53's were painted brown for the camoflauge effect of the Iranian desert and to be similar to Iranian aircraft paint schemes.

HM-16 provided the eight helicopters for Eagle Claw and was until 19 May 1980 when the squadron returned to Norfolk after an unprecedented 193 days continuous at sea.

Go!

Operation Eagle Claw launched on the evening of 24 April 1980 when six C-130s left Masirah Island, Oman, and eight RH-53D

helicopters departed the USS Nimitz in the Arabian Sea. Both formations headed for the

location code-named Desert One.

First Problems

A month before the assault a CIA Twin Otter aircraft had flown to Desert One.

A USAF Combat Controller had rode around the landing area on a

light dirt bike and planted landing lights to help guide the force in.

That insertion went well, with no contact, and the pilots reported that their sensors had picked up some radar signals at 3,000 feet but nothing below that.

That insertion went well, with no contact, and the pilots reported that their sensors had picked up some radar signals at 3,000 feet but nothing below that.

Despite these findings, the helicopter pilots were told to fly at or below 200 feet to

avoid radar. This limitation caused them to run into a haboob, or dust storm, that they

could not fly over without breaking the 200 foot limit. Two helicopters lost sight of the

task force and landed, out of action. Another had landed earlier when a warning light

had come on. Their crew had been picked up but the aircraft that had stopped to retrieve

them was now 20 minutes behind the rest of the formation.

Battling dust storms and heavy winds, the RH-53's continued to make their way to

Desert One. After recieving word that the EC-130's and fuel had arrived, the two aircraft

that had landed earlier started up again and resumed their flight to the rendevous.

But then another helicopter had a malfunction and the pilot and Marine commander decided

to turn back, halfway to the site. The task force was down to six helicopters,

the bare minimum needed to pull off the rescue.

The first group of three helicopters arrived at Desert One an hour late, with the rest appearing 15 minutes later. The rescue attempt was dealt it's final blow when it was learned that one of the aircraft had lost its primary hydralic system and was unsafe to use fully loaded for the assault. Only five aircraft were servicable and six needed, so the mission was aborted.

The first group of three helicopters arrived at Desert One an hour late, with the rest appearing 15 minutes later. The rescue attempt was dealt it's final blow when it was learned that one of the aircraft had lost its primary hydralic system and was unsafe to use fully loaded for the assault. Only five aircraft were servicable and six needed, so the mission was aborted.

And there were other problems. A bus came by on a dirt road shortly after the lead

C-130 landed. Its driver and about 40 passengers were held until the Americans left.

With the mission already aborted, things got worse when one of the helicopters moved to another position and drifted into one of the parked EC-130's. In the pilot's defense, it was dark and his rotors kicked up an immense dust cloud, making it difficult to see but immediately both the C-130 and RH-53 burst into flames, lighting up the dark desert night, and 8 crewmembers lost their lives.

Disaster

With the mission already aborted, things got worse when one of the helicopters moved to another position and drifted into one of the parked EC-130's. In the pilot's defense, it was dark and his rotors kicked up an immense dust cloud, making it difficult to see but immediately both the C-130 and RH-53 burst into flames, lighting up the dark desert night, and 8 crewmembers lost their lives.

List of Eagle Claw casualties:

CAPT Harold L. Lewis Jr. - USAF EC-130E A/C Commander

CAPT Lyn D. McIntosh - USAF EC-130E Pilot

CAPT Richard L. Bakke - USAF EC-130E Navigator

CAPT Charles McMillian - USAF EC-130E Navigator

TSGT Joel C. Mayo - USAF EC-130E Flight Engineer

SSgt Dewey Johnson - USMC RH-53D Crewmember

Sgt John D. Harvey - USMC RH-53D Crewmember

Cpl George N. Holmes - USMC RH-53D Crewmember

CAPT Harold L. Lewis Jr. - USAF EC-130E A/C Commander

CAPT Lyn D. McIntosh - USAF EC-130E Pilot

CAPT Richard L. Bakke - USAF EC-130E Navigator

CAPT Charles McMillian - USAF EC-130E Navigator

TSGT Joel C. Mayo - USAF EC-130E Flight Engineer

SSgt Dewey Johnson - USMC RH-53D Crewmember

Sgt John D. Harvey - USMC RH-53D Crewmember

Cpl George N. Holmes - USMC RH-53D Crewmember

The C-130 was evacuated and the order came to blow the aircraft and exfiltrate the country.

However, in the dust and confusion the order never reached the people who would blow the

aircraft. There were wounded and dying men to be taken care of and the aircraft had to be

moved to avoid having the burning debris start another fire. Because of this failure to

destroy the helicopters, the Americans left behind them 5 RH-53D intact and top secret plans

fell into the hands of the Iranians the next day and the agents waiting in-country to

help the Delta operators were almost captured.

"A few days ago the President made a very courageous decision as he ordered us to execute the rescue operation as we tried to free our Americans held hostage in Teheran. It was not a risk-free operation-there is no such thing as a risk-free operation..... we all shared considerable disappointment that we were not successful. But let's not be despondent about that. Our job is now to remain alert, to look for those opportunities, times when we can bring our Americans out. Our job is to stay ready."

Admiral Thomas B. Hayward, Chief of Naval Operations,

in a video message to USS Nimitz, USS Texas and USS California during their transit home from the Indian Ocean.

After Eagle Claw a long negotiation follows, including the beginning of the Iraq-Iran war.

Was on 19 January 1981 when Secretary Christopher signs the accord at 3:35 E.S.T. and on

January 20, after last-minute delays over fund transfers,

the hostages leave Teheran on the 444th day of their captivity, minutes after President Carter

leaves office. On January 21, citizen Carter greets the hostages at Weisbaden, West Germany.

Operation Honey Badger which was to be the second attempt to rescue the hostages from Iran was no longer necessary.

Amazon books

Find more Operation Eagle Claw books

A six-member commission was appointed by the JCS to study Operation Eagle Claw events. Headed by Adm James L. Holloway III, the panel included Gen LeRoy Manor, who commanded the Son Tay raid, November 21, 1970 in Vietnam to rescue prisioners. One issue investigated was selection of aircrew. Navy and Marine pilots with little experience in long-range overland navigation or refueling from C-130s were selected though more than a hundred qualified Air Force H-53 pilots were available. Another issue was the lack of a comprehensive readiness evaluation and mission rehearsal program. From the beginning, training was not conducted in a truly joint manner; it was compartmented and held at scattered locations throughout the US. The limited rehearsals that were conducted assessed only portions of the total mission. Also at issue was the number of helicopters used.

The commission concluded that at least ten and perhaps as many as twelve helicopters should have been launched to guarantee the minimum of six required for completion of the mission. The plan was also criticized for using the "hopscotch" method of ground refueling instead of air refueling as was used for the Son Tay raid. By air refueling en route, the commission thought the entire Desert One scenario could have been avoided.

Although the results of the mission were tragic, Operation Eagle Claw's contribution to the American military was invaluable. The lessons learned from the mission illustrated serious deficiencies in the capability of the American military. The mission forced the political and military leadership to address these inadequacies and initiate changes. Military reforms would be complete and revolutionary. In particular, the mission was a major contributor to the changing of service parochialism. The mission contributed to the development of Jointness.

RH-53D serial number 158761 destroyed in collision with EC-130E BuNo 62-1809

RH-53D serial number 158761 destroyed in collision with EC-130E BuNo 62-1809

Five more RH-53D abandoned or destroyed at Desert one.

Five more RH-53D abandoned or destroyed at Desert one.

See also:

- RH-53D Production List

- Eagle Claw memories

Operation Honey Badger which was to be the second attempt to rescue the hostages from Iran was no longer necessary.

Find more Operation Eagle Claw books

The Lessons

A six-member commission was appointed by the JCS to study Operation Eagle Claw events. Headed by Adm James L. Holloway III, the panel included Gen LeRoy Manor, who commanded the Son Tay raid, November 21, 1970 in Vietnam to rescue prisioners. One issue investigated was selection of aircrew. Navy and Marine pilots with little experience in long-range overland navigation or refueling from C-130s were selected though more than a hundred qualified Air Force H-53 pilots were available. Another issue was the lack of a comprehensive readiness evaluation and mission rehearsal program. From the beginning, training was not conducted in a truly joint manner; it was compartmented and held at scattered locations throughout the US. The limited rehearsals that were conducted assessed only portions of the total mission. Also at issue was the number of helicopters used.

The commission concluded that at least ten and perhaps as many as twelve helicopters should have been launched to guarantee the minimum of six required for completion of the mission. The plan was also criticized for using the "hopscotch" method of ground refueling instead of air refueling as was used for the Son Tay raid. By air refueling en route, the commission thought the entire Desert One scenario could have been avoided.

Although the results of the mission were tragic, Operation Eagle Claw's contribution to the American military was invaluable. The lessons learned from the mission illustrated serious deficiencies in the capability of the American military. The mission forced the political and military leadership to address these inadequacies and initiate changes. Military reforms would be complete and revolutionary. In particular, the mission was a major contributor to the changing of service parochialism. The mission contributed to the development of Jointness.

Eagle Claw identified Helicopters

See also:

- RH-53D Production List

- Eagle Claw memories